- Home

- Amaryllis Fox

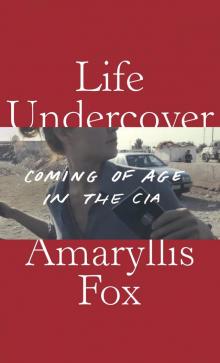

Life Undercover

Life Undercover Read online

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2019 by Amaryllis Fox

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names, locations, and operational details have been changed to safeguard intelligence sources and methods.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fox, Amaryllis, author.

Title: Life undercover : coming of age in the CIA / Amaryllis Fox.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009838 (print) | LCCN 2019020223 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525654988 (Ebook) | ISBN 9780525654971 (hardback) | ISBN 9781524711665 (open market)

Subjects: LCSH: Fox, Amaryllis. | Terrorism—Prevention—Government policy—United States. | United States. Central Intelligence Agency—Officials and employees—Biography. | Women intelligence officers—United States—Biography. | Intelligence officers—United States—Biography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Military. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women. | TRUE CRIME / Espionage.

Classification: LCC JK468.I6 (ebook) | LCC JK468.I6 F69 2019 (print) | DDC 327.12730092 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009838

Ebook ISBN 9780525654988

Cover image courtesy of Amaryllis Fox

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

v5.4

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Acknowledgments

A Note About the Author

For my mum, who taught me to live without cover

1

In the glass, I can see the man who’s trailing me. I first noticed him a few turns back, his path correlated with mine in the mess of Karachi back alleys. Our reflections mingle in the tailor’s window. He is horse-faced and tall. His palms open and close as he walks. “The security of the veil,” a poster reads, above burqas and hijabs.

Ahead of me, the bus I’d planned to board comes and goes, covered in an ecstasy of pigment and pattern. Every square inch is painted with bright shapes and swirls, intricate and infinite, like a Mardi Gras parade float, a diesel temple to the pleasure of the eye. It has the look of a free thing burdened, a slow-lumbering dragon, weighed down by its own beauty and the commuters that hang from its belly and back. They are my favorite thing about Pakistan, these buses. Against the dust and the smog and the honking of horns, they are startling, like the discovery of a kindred soul behind the otherwise dull face of a stranger.

It won’t delay me long, letting this one lumber by. Another will come through in a few minutes on its way to M. A. Jinnah Road. Better not to give Mr. Ed the impression that I’m trying to lose him. Nothing raises suspicions more than shaking surveillance. It’s what always makes me laugh about the CIA operatives in the movies. All the roof gymnastics and juggling of Glocks. In real life, one chase sequence through a city center and my cover would be blown for life. Better to lull them into a false sense of security. Walk slowly enough for them to keep up. Stop at yellow lights when driving. Give them a good look each time I come and go. In other words, bore them to tears. Then slip out and save the Bond business for when they’ve been left to tranquil sleep.

I can see Mr. Ed fiddling with cooking utensils at a market stall while we wait. It’s not clear which flavor of surveillant he is. First guess is usually the local service—a counterintelligence officer from the government of whatever country I’m in. But in this case, I’m not so sure. Pakistani intelligence operatives are good at what they do. Their surveillance teams are usually six or seven strong, so that they can swap out the guy who’s trailing me every few turns to minimize the chance that I’ll notice. This man seems to be alone. Not only that, but there’s a foreign angle to his face. Despite his traditional dress, the kameez worn long and loose over his trousers, he has the air of central Asia about him. A Kazakh, maybe, or an Uzbek. Most likely, he’s checking me out in preparation for tomorrow’s meeting. Al Qa’ida has had an influx of central Asian recruits of late. Putting newcomers to work as spotters is pretty typical. Gives them a chance to learn the city while the group’s recruiters size them up.

I watch him weave his way through the stalls that line the side of Jodia Bazar. He picks up part of a carburetor and turns it around in his hands. Something about the way he examines it makes me wonder whether maybe he’s of the third variety—an aspiring arms broker who knows I work with Jakab, the Hungarian purveyor of all things Soviet surplus. Of course, there’s always the underwhelming fourth possibility: he’s a plain old would-be predator, eyeing a twenty-eight-year-old American girl traipsing through foreign streets alone. After all, there’s Occam’s razor to consider. The simplest explanation is usually the right one.

Government or goon, any tail is cause to abort an operation. No sense meeting a source or picking up dropped documents with an audience in tow. Even harmless creeps can turn less harmless when they think they’ve witnessed something worth telling. Luckily, I’m not on my way to an operational act. Not until tomorrow. Today is pure reconnaissance.

Jakab told me the intersection of Abdullah Haroon and Sarwar Shaheed. That was all he knew, he said. He wasn’t even supposed to know that. He’d probed his buyers for the info, under the guise of selling them the right bomb for the job. He’d need to understand the target, he told them, to be sure the material would be enough to register on a Geiger counter. Enough to win them the attention they sought.

When the next bus arrives, I board slowly and easily, as if I’m not headed to check out the target of a potential nuclear terror attack. Mr. Ed climbs up top, to sit on the roof. I take a seat in the women’s compartment. Outside, the afternoon is fading into gloaming and the motorbikes begin to turn on their lights. There’s time, amid the crush of evening traffic, to take in the buildings, most of them older than the country itself, monuments to a time when Pakistan and India were one, the plaything of colonists and kings. I feel the kinship of it, being a Yankee. The shrugging off of England’s yoke. I can picture the men and women around me tossing crates of tea into the ocean in their kameezes and shawls. We are rebel lands, they and us. If only all that rebellion didn’t spill quite so much blood.

I can see the intersection emerge from the traffic and the donkey carts, up beyond the faded tarps, strung taut between buildings to lend shelter from the now-set sun. On one side is the National Bank of Pakistan, a reasonable guess at their objective, I suppose. After all, the mullahs cleared the twin towers as legitimate military targets, claiming that America kills Muslims as much by impoverishing the innocent as it does by tan

k treads on the ground. But the building doesn’t feel right to me. It’s concrete and uninspiring, postwar brutalism at its most scathingly bare. It doesn’t exactly scream Western excess.

I wait until the driver slows and jump back into the dust of the city. Mr. Ed lands softly on the far side of the bus. I cross Abdullah Haroon Road slowly enough for him to follow, and then it dawns on me as I reach the other side. In front of me, set back slightly behind chained gates, is what looks to be a miniature castle, a tiny stone fortress amid the rickshaws and pigeons. It’s the Karachi Press Club, the bastion of free speech and independent journalism, famed home to protest, debate, and the only bar serving alcohol in the country. Dollars to doughnuts, this is their target. Nothing like getting bombed to get you bombed in this town.

From what Jakab said, this attack would be intended as a warning—a shot across the bow of any country where the press flows as free as the booze. Clean up Pakistan first, then turn attention to the infidel. It’s an elegant positioning, but the truth is that it’s a lot easier to plan and execute an attack here than in Times Square. Al Qa’ida’s been working toward a nuclear capability since at least 1992, when Usama bin Laden sent his first envoys to Chechnya in search of fissile material lost in the crumbling Soviet shuffle. But washed-up nukes are elusive, expensive, and highly temperamental. Makes sense they’d aim for a dry run close to home.

That means I’m looking at two scenes simultaneously: first, the potential attack in front of me and, second, the implications for a follow-up attack on U.S. soil. Writers and thinkers from across the world come to speak at the Karachi Press Club, including Americans. A ten-kiloton nuclear weapon would vaporize every building and every person I can see for half a mile. Detonated outside the New York Times building in midtown Manhattan, the same device would incinerate Times Square, Penn Station, Bryant Park, and the New York Public Library, plus countless apartments, bodegas, preschools, and taxicabs in a blast burning hotter than the sun. Because light travels faster than sound, the half million or so people in that first radius would turn to vapor before they even heard a boom. For another half mile in every direction, radiation would kill most people within days. Cancer would ravage their outer neighbors for years yet to come.

Terrorism is a psychological game of escalation. It’s not the last attack that scares people. It’s the next one.

Think it’s frightening to see our embassies hit overseas, as they were in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998? Try watching a fortified battleship blown up on active duty, as our USS Cole was in the Gulf of Aden two years later. Think a strike on our military is scary? How about a mass-casualty attack on our homeland, like the one we watched unfold in horror on a cloudless Tuesday morning the following September.

The question for al Qa’ida since 9/11 has been where to go from there. What could offer more haunting imagery than jetliners plowing into skyscrapers? What could be more destructive than killing three thousand people on a random Tuesday morning? Eventually the only thing left is a mushroom-shaped cloud. Eventually the only viable escalation is a blast so bright, the few surviving witnesses will see its image burned on their retinas for the remainder of their lives.

Mr. Ed is watching a woman walk through the Karachi Press Club gates. Her head is covered with a 1970s Pucci-style scarf. The bottom of her kameez is patched with flowers. The whole look is demure and Islamic with a joyful Partridge Family wink. Beside the gates, a man sells flowers, cut and bunched. He shouts discounted prices at drivers’ windows. On the sidewalk behind him, there’s a sign for a children’s dentist.

I feel the horror of it froth inside me. The evisceration. The hideous, useless waste of potential. I want to run at the horse-faced man, want to rush him and shake him and ask him how he can consider killing a woman who sews flowers onto her clothes. How he can consider killing half a million like her. But for all I know, he’s a run-of-the-mill street stalker. I’ll have my chance tomorrow. One shot to tell al Qa’ida why they shouldn’t detonate a nuclear weapon in a major city center. One opportunity, face-to-face with the group that wants to bring this country to its knees.

Leave the man alone, I figure.

Then he takes out a mobile phone and makes eye contact with me as he dials.

2

My dad is like a spreadsheet: logical, data-driven, and capable of crunching as many inputs as he’s given. He’s American, raised in Franklinville, New York, a town so small and insular, he was among only a few kids in his graduating class to go to college. He went to the University of Chicago and became one of the youngest economics professors in its history. By the time my older brother, Ben, and I come along, he’s advising foreign governments on energy policy in every corner of the globe, which means we see him mainly on his way to and from the airport.

In those early days, my mom’s more like an Impressionist painting: beautiful, proper, and destined to someday—though then not yet—slip the rules of form and burst into her own abstract truth. She is the color in our coloring book, the aliveness in our mornings, noons, and nights. She’s English. And like all Brits, she grew up marinated in tradition and protocol. In my earliest memories, she’s still bound by the rules of class that permeate the social circles of English country manors. A wild poet in her youth, her mother reined in her fierce brilliance, taught her the importance of the right habits, the right language, the right education, to flourish in the strange waters of British aristocracy. And in my earliest memories, she still wonders whether to pass those rules along. A gift of love for we children who are her everything. But an artist still at heart, she opts instead to let us be blank canvases, and slowly, bravely, comes to let our color live outside the lines.

My brother has learning differences. Sometimes they mean he doesn’t sense the lines at all. Wildly clever, but challenged in motor skills and speech, he’s mercilessly teased by the banal bullies of our school in Washington, D.C. My mom is determined to mend Ben’s differences for fear others might be cruel, might categorize him as the wrong sort or think of him as different.

Like a Sherpa, determined to get her charge over Everest’s peak, Mom sits patiently with Ben at our little kitchen table, math book open to a sea of numbers he complains won’t sit still on the page. They move about like pixies, he says, and I watch from the cupboard under the sink, in case one flies up in the air where I can see it. I’ve converted the cupboard into a playhouse, with pictures of clouds on the wall made from dried Elmer’s glue. Every so often, my brother gives up feigning understanding when he knows there is none and turns to my hideaway in exhausted despair. I hold up our old terrier Snowy’s paw in a solidarity salute or make our pet hermit crabs chant his name in the air until finally he cracks a big toothy grin and my mother laughs her beautiful laugh and they stop to make popcorn—the kind with the built-in frying pan that swells like a pregnant belly on top of the stove.

On the weekends, Ben and I roam happily around the Smithsonian, just the two of us. Mom drops us off across from Uncle Beazley, the hollow fiberglass triceratops, with horns polished pale by a thousand climbing hands. She synchronizes our watches, gives us solemn instructions about cars and strangers (even if they say they have puppies), and calls out how much she loves us as we bound up the stairs.

We watch the Gilgamesh movie in the Mesopotamia room of the natural history museum. It’s stop-motion animation, with clay characters that jolt as they walk. At the Air and Space, we eat dehydrated ice cream and watch the Man in the Moon talk about history and war and the changes he’s witnessed from his spot in the sky, which, my brother points out, makes the Gilgamesh story seem like one little stripe in a big Neapolitan sundae.

When the weather’s nice, we hang around at the Lincoln Memorial and take turns reciting the Gettysburg Address, wearing traffic cones as top hats. Then five minutes before our synchronized minute hands approach five p.m., we race back to the infinity sculpture and our mom’s waiting car. The undergroun

d parking lot’s been closed. To make it harder to plant a bomb, Mom explains.

I start school and learn that Ben differs from other kids in ways I think make him cool and they think make him prey. He walks with a quirky stiffness. “Like a freak,” the bullies sneer. “Like Gilgamesh,” I tell him. On the playground, he spends recess sitting in the shade of a tree, humming strange pieces of music with long gaps of silence in them. The other kids think he has a screw loose, but I know he’s just working his way through whichever symphony my dad’s played on our record player the night before. Humming each instrument’s part from beginning to end. Violin, then clarinet, then kettledrums. He takes music apart the way a tinkerer deconstructs a radio. Can hear how it all fits together in his head.

“Every village needs an idiot,” the bullies laugh.

Every genius is misunderstood.

In the evenings, Mom reads to us. Paddington and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and The Wolves of Willoughby Chase. She does all the voices, stopping only when she’s made us laugh or cry so hard she can’t help joining in. Then we all collect ourselves and dive back into the pages, which dance and flicker around us, until finally our pleas for one more chapter run out and we drift to sleep in lands far away from math books and schoolyard bullies. “Never forget,” she tells us softly, “you can travel anywhere, just by closing your eyes.”

When I am seven and Ben is ten, we save up cereal box tops to send away for a cardboard haunted house. It comes in a flat pack and we set it up in our basement, slotting the pieces together until we have our own spooky castle, between the washing machine and the stairs.

Life Undercover

Life Undercover